H S Pyne - an Appraisal

As one of the longest-serving headmasters of Warwick School in the twentieth century, it is, perhaps, now a good opportunity to evaluate his impact upon the school. There are various features of his life, not always happy ones, which may have affected his work here.

Horace Seymour Pyne was born in 1863 (or 1864, in an entry in the Staff Register in his own hand – more on this later) and was a pupil of Lancing School, where his father was headmaster, from 1874 to 1881. He did not immediately attend university but found employment as an Assistant at the Grocers’ Company’s School in London from 1883 to 1885. King William’s College on the Isle of Man employed him as a science master from 1885 to 1899, and from there he was appointed as headmaster of the King’s Middle School in The Butts, Warwick, in 1899. The first inkling that we get of Pyne’s ruthless nature was that, on his appointment to the Middle School in 1899, he sacked all the existing staff. Exactly the same happened in 1906, when he arrived at Warwick School.

His first love was physics, and the Middle School soon became a Centre of Scientific Excellence – and a direct threat to our older grammar school the other side of the River Avon. He seems to have been keenly aware of the competition between the two schools, and we still have, in the school archives, Pyne’s two scrap books in which he pasted cuttings of every single newspaper article concerning either school up to 1906. He was, of course, the first headmaster of Warwick School not in holy orders, and his sense of reforming zeal was quite evident in September 1906, when he was parachuted into the job, his predecessor, Rev. W. T. Keeling, having fled the previous Easter.

Having finally decided to start his university education, Pyne merely matriculated (as an external student) at London University in 1891. His first full degree, a BA from Dublin (again external), was obtained while he was still working on the Isle of Man. Pyne went on to collect Irish degrees by the handful – all externally: a BSc from the RUI in 1897, a BA from TCD in 1915, and an MA, also from TCD, in 1918. He was a good friend of Sir Oliver Lodge, the first principal of the new Birmingham University, and he spent time there in summer holidays conducting research – complaining that he couldn’t finish one project because the university had been turned into a military hospital in the First World War. He then carried on his work, particularly on radioactivity, in Warwick School’s science department – now the music block. Pyne was also a skilled photographer and gave regular lantern slide lectures to the boys in Big School. Some of these slides were hand-coloured.

Pyne cocked further snooks at the Board of Education while at the Middle School by taking in boarders (it was supposed to be a day school, for educating boys for commerce), in starting a sixth form, and even changing the name of the school, in 1905, to the King’s County School. The Board retaliated by reporting that “there is evidence of a deliberate intention on the part of the authorities of the Middle School unduly to compete with the Grammar School.” This competition, aided and abetted by inadequate headmasters from 1896 onwards, and an extremely partisan Earl of Warwick, Chairman of Governors, led to the economic collapse of Warwick School in the summer of 1906, just as the celebrated Warwick Pageant was reaching its final performances – and with all the pupils of the school taking part.

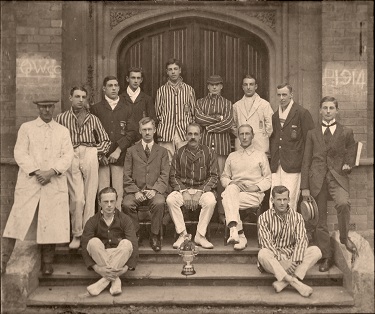

On 19 September 1906 220 boys were enrolled, with a teaching staff of 12 – term started at 10am, and an entrance examination was held an hour later. It has to be said that the lack of confidence that the existing parents of pre-1906 pupils had in H. S. Pyne meant that only 13 boys from the old grammar school signed up to the new regime. Incidentally, it would not have pleased Rev. W. T. Keeling at all to have found out that the financial deficit got even worse in the first few years of H. S. Pyne’s headship – it had reached well over £2,000 by 1910.

The school was being modernised almost from the start of Pyne’s time. Electric lighting was installed during 1910, and teaching rooms dedicated to just one subject were being developed, starting with history in 1910. The long-awaited outdoor swimming pool was ready for the first school swimming sports in 1912. Also, in December 1912 the whole school had paraded to St Mary’s Church, banners included, for a service “to perpetuate and revive the bond of connection” between the two institutions. The modern annual Carol Service in St Mary’s might, therefore, be said to derive from this 1912 revival.

For various reasons, the school thrived as never before during the First World War, and there was a significant rise in pupil admissions: numbers reached 200 in 1916, and, towards the end of the war, this process accelerated to such an extent that the school rose in size to over 300. Suitable premises and staff lagged behind, however. This rise coincided with the school starting to take in highly-subsidised day-boys from Warwick and Leamington, sponsored by the Local Authority, and this scheme did a great deal to alter the social composition of the pupil cohort. There were eight free-place boys in 1914, rising to 26 by 1919. Between 1906 and 1927 the teaching staff expanded from 12 to 25 in number to cope with higher pupil numbers. Pyne’s appointment in 1906 was said to be “without prejudice”, but his effect on pupil numbers, and his vigorous building and modernisation programme, convinced the governors to quietly appoint him “formally, without advertisement”, in 1909.

Tragedy for the Pyne family was never far behind, however. H. S. Pyne had married London-born Hannah Huxley Sibley (1861 – 1955) in July 1885, in Hackney, and all of their five children were born in Castletown, on the Isle of Man. Their eldest son, Orry, who may have had learning difficulties, died in 1927, aged 40. Their elder daughter, Mona, died in 1901 at the age of 12, and their youngest son, Eric, died in service in 1917, aged 20, when his ship was torpedoed off Gallipoli. Their elder daughter, Ethel, married a stockbroker in 1918, but didn’t have any children, and their surviving son Arthur married Eva Scarr, the step-daughter of A. D. Hainworth (WS staff 1907–38), but the marriage didn’t last more than a few years, and they were also childless. This Mrs Pyne became a great friend of the Ridings after 1928.

Eric Wilfred Pyne’s death precipitated his father’s financing the building of the chapel gallery at Warwick School, commissioning the First World War Memorial (which was originally placed along the front of the gallery) and offering a space in the west wall of the chapel to a 23-year-old student, Francis H. Spear, which became the home of Spear’s final diploma piece from the Royal College of Art in 1925. It is a perplexing matter that this window, a deeply-felt tribute to Eric Wilfred Pyne and all the other Old Warwickians who fell in the War, contains jokes, some only recently discovered, fused and etched into the glass.

Another extraordinary facet of this window is the crest at the bottom of the central panel – Pyne took it upon himself to design a new school crest, and had it placed prominently not only in this window, but also the smaller Spear windows formerly in the vestry, and now in the main body of the chapel. He seems to have done this without any consultation with the Governors, who were appalled, let alone via the official route through the College of Arms. It was Pyne’s successor, G. A. Riding, who organised the official granting of the modern, and quite different, school crest in the early 1930s.

Pyne started a school orchestra in 1915 – five violins, a cello, a piccolo, a piano and two drums – and started joint debates with King’s High School for Girls in 1916. The Town Crier had visited in 1912 “according to custom”, but there is no record of it having taken place at Warwick School before that date. In 1916 Pyne started the annual Science Exhibition, a feature, on and off, for the next 50 years. The installation of electricity in the late Edwardian era allowed films to be shown in Big School, and these were hugely popular, with pupils providing piano accompaniment to the silent films.

Crises came from unexpected quarters, starting in 1913, when Pyne narrowly avoided legal action over awarding the valuable Fulke Weale Exhibition to the wrong boy. In May 1914 came an appalling sanitary report on the whole school from the Medical Officer of Health, and a few months later, in December 1914, H. M. Inspector of Schools produced a severely critical report, citing “serious defects in the organisation of the school” and “unrest among the Staff”. Pyne’s rejoinder was that “there are no suitable Masters to be had; a few old men are willing to fill up gaps for a term or two”. Pyne was given until May 1916 to remedy the defects, but the planned re-inspection was continually postponed until 1921, when the inspectors said, “the Headmaster was to be congratulated upon the social life of the School, the tone and discipline of which was good.” They did add, however, that “the time was arriving when the school would require increased vigour and drastic reorganisation” – the main point seeming to be that the teaching staff should be reduced in number.

An unexpected skill on H. S. Pyne’s part was as a producer of Shakespeare plays. The school’s Literary and Dramatic Society was founded in 1919, and, thanks to a large increase in the number of boys at the school during the First World War, this, together with the enthusiasm of the newly-formed Society, must have prompted Pyne to start his programme of producing Shakespeare plays. In December 1919, therefore, we learn from Portcullis magazine that there were three performances “at the school” of Twelfth Night. The school did not possess a stage at this time – some sort of temporary structure must have been assembled in Big School. The cast was all-male, as it would have been in Shakespeare’s time.

The tradition had been set, therefore, for a Shakespeare production at the end of every Christmas term – in 1920 came Julius Caesar, also performed at the school, it would seem. Between 1921 and 1924 the school used the now-demolished County Theatre in St Nicholas Church Street for its productions: in 1921 came Henry V, in 1922 Henry VIII, in 1923 The Merchant of Venice and in 1924 Richard II. The first three of these performances, though, were for one night only. It must have been exhausting for the cast to play Richard II twice on the same day in 1924.

In an interesting note in Portcullis, we learn that Miss M. L. Tibbits (WS staff 1921 – 24, an Old Girl of King’s High School from 1910 to 1917 and who was employed to teach piano and drawing) “sang very sweetly in Act III” of The Merchant of Venice, “and who was responsible for the designing of the dances.”

By 1925 a stage had been constructed at The Limes end of Big School, and two performances (on the same day) were made of King John. In 1926 came Coriolanus and in 1927 Richard III, which was H. S. Pyne’s last production before he retired. Christmas 1928 saw a repeat performance of Julius Caesar, with purely teaching staff on the production side. The whole scheme started to unravel at Christmas 1929, when an outbreak of mumps decimated the acting body. Four adults stepped in, and one of them was the very young wife of the new headmaster, G. A. Riding, who played “a gallant and gracious” Viola to F. G. Macaskie’s “manly and direct” Sebastian. Whatever happened (and it would seem that quite a lot happened) that was the end of this run of Shakespeare plays, which re-started two headmasters later in 1937.

There are two surviving buildings from Pyne’s time – the Engineering Workshop of 1910 and the wooden Pavilion of 1927, built to replace a Victorian one which burned down in 1924. “New Buildings”, erected to cater for increased pupil admissions, lasted from 1918 to 1974. The statue of King Edward the Confessor, paid for by the Old Warwickian Association and placed in a niche opposite the main entrance in 1924, was moved onto the first-loor landing more than 90 years later.

It has to be said that Pyne’s financial management of the school, in what must be called collusion with the man with whom he worked for decades, M. M. Clark, and who became his deputy in the early 1920s, benefited them both to a large extent. The financial system used by the school from 1906 onwards seems to be that the day boys paid their fees to the Bursar and were subsidised by the Charity Commission and by grants from the Education Department, while the boarders paid their fees, which were five times that of the day-boy fees, direct to the headmaster. Day-boy fees in the 1920s were £18 per year, while boarding fees were £72, plus the £18 tuition, per year. It seems certain that Pyne did very well financially from this arrangement – rather better than he was prepared to let on. Figures show that the headmaster was allowed to keep £54 of the £72 boarding fee – and the less he fed the boarders, the more profit he could make. He also crammed in – somewhere – double the permitted number of boarders; there were 146 in 1921. Some were housed in M. M. Clark’s attic on the Emscote Road. There is the distinct possibility that, for Pyne and Clark, the money just poured in, with very little checking by the governors, despite Pyne telling them in 1927 that “he made practically no profit on the boarders”. He made so much, in fact, that, before he retired, he commissioned an architect-designed Tudor-style retirement mansion, Sheen Lodge, opposite Sheen Gate, Richmond Park, “complete with ingle nooks, a vast hall and a musicians’ gallery” – and two acres of land. Indeed, in 1933, the governors minuted: “The Governors should reserve the right of seeing the Headmaster’s annual Boarding House profits.” Pyne never lived in the house but sold it – it was later occupied by Rudolf Nureyev, among others. The original Sheen Lodge, incidentally, had been given by Queen Victoria to Sir Richard Owen, the scientist who coined the term “dinosaur”, in 1852.

A different sort of problem developed in the later years of Pyne’s reign – the school had a serious problem with rats between 1927 and 1928. Dennis Castle, a boarder between 1926 and 1929, recalled:

The rats became such a pest that the rat-catcher was called in. He had some success, and I remember him once emptying a sack of squirming bodies on the cricket square - with his large Airedale polishing them off, one by one, hurling them broken-backed into the air. He never missed one.

Then the rat-catcher tried poison. This resulted in one dying under the floorboards by Hainworth's seat in chapel. Poor Hainy - he sat through a lengthy Pyne sermon, a handkerchief pressed to his nose, sweat glistening on that noble brow. Never was there a more appalling stench. Another had died within the organ, and the last hymn had one verse only, before the congregation literally left at the double - to a very abridged version of War March of the Priests.

Whitlam and the science department experimented with poisons, too, and the rat population started to diminish. But the moment Riding took over, in the summer of 1928, the rats were never seen again. Senior boys quipped that Pyne had taken them with him, but we seem to have owed a lot to Riding for that Easter holiday clean-up.

The same pupil recalled that in the summer of 1927, Mr and Mrs Pyne were apparently stopped by HM Customs officers at Dover, returning from a weekend in Paris, and carrying dutiable goods which they had not declared. Mrs Pyne took the blame during court proceedings, and Pyne gave notice to the governors that he would leave at Christmas. A replacement headmaster could not be found that quickly (G. A. Riding was offered the post on 2 December 1927 but had to have time to give notice himself at Rugby School) and so Pyne served one more term before leaving at Easter 1928, aged 65. But perhaps he altered his birth year in the Staff Register to 1864, in order to make it appear that he was not yet of retirement age?

Pyne returned to the school twice – in 1940, to present the prizes, and in 1949, to see his portrait being presented to the school. He died on 4th July 1950, aged 87, leaving his estate, worth just over £7,000, to his two surviving children.

In 2000, the old Big School, which had, since 1970, been the school library, was re-named the Pyne Room.

G. N. Frykman

June 2022